The Color of Bias - Part 3

GS

The Color of Bias: Kodak, Racial Representation, and the Intersection of Technology, Race, and Media - Part 2

Welcome to the third installment of my essay exploring the intersection of technology, race, and media, focusing on Kodak's influential role in the film industry and the racial biases embedded in its color science and technological choices. If you haven't read Part 1 and Part 2, I would encourage you to start there. PART 1 can be found here: https://freeelectronmedia.com/blog/the-color-of-bias. PART 2 can be found here: https://freeelectronmedia.com/blog/the-color-of-bias---part-2

Kodak's market dominance was not just a result of its technological innovations but also of its strategic business practices. The company invested heavily in marketing and distribution, ensuring that its products were widely available and trusted by both consumers and professionals. This dominance allowed Kodak to set industry standards, which had extensive implications for the global photography and film industries.

One of the key factors behind Kodak's market dominance was its ability to control the entire photographic process, from the production of film and cameras to the development and printing of photographs. This vertical integration allowed Kodak to ensure that its products were used consistently across the industry, further entrenching its technological standards.

Kodak's dominance was also bolstered by its extensive marketing campaigns, which positioned the company as the leading provider of photographic technology. These campaigns were aimed at both amateur and professional photographers, as well as at cinematographers and film studios. By establishing itself as the industry leader, Kodak was able to influence the development of industry standards, particularly in the areas of film chemistry and color balance.

However, Kodak's dominance had significant drawbacks, especially in how non-white individuals were depicted in visual media. As the leading producer of film stock, Kodak played a key role in setting industry standards, influencing everything from camera design to lighting techniques. Its products became the default choice across a wide range of applications, from Hollywood films to everyday photography. While this standardization helped popularize photography, it also reinforced the biases embedded in Kodak's technology and color science, amplifying their negative impact on the portrayal of racial diversity in visual media.

1.6 The Rise of Color Film and the Specific Choices Kodak Made

The rise of color film in the mid-20th century was a watershed moment in the history of photography and cinema. As color film became more accessible, it began to replace black-and-white film as the dominant medium for both amateur and professional photography and film production. Kodak, as the leader in the market, made specific choices in the chemistry of its color film stocks that had significant implications for racial representation.

Kodak’s choice to optimize film chemistry for lighter skin tones was not necessarily a conscious decision aimed at excluding non-white subjects, but the long-term outcome was the same: The technical limitations embedded in Kodak's film stocks meant that darker skin tones were poorly represented, often appearing underexposed or with unnatural color casts.

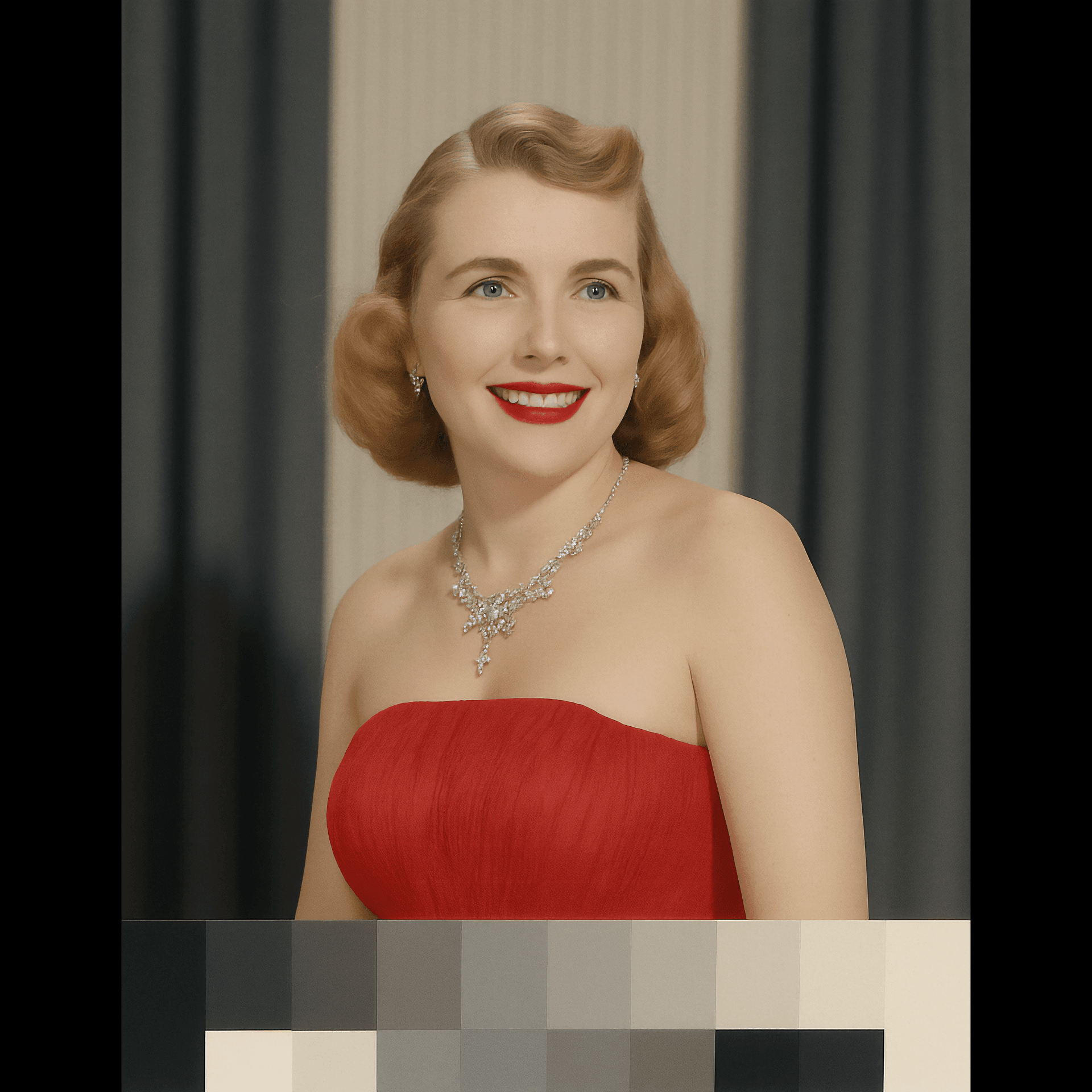

One of the key reasons for this bias was the use of "Shirley Cards," which Kodak used for color calibration. These cards featured images of white women and were employed to set the standard for color balance in film processing. Consequently, the complexion of the women on the Shirley Cards became the reference point for "correct" exposure and color balance. In addition to Shirley Cards, the practice of using "China Girls" in motion pictures further reinforced this bias. These images of fair-skinned women, used in film leader sequences for color testing in cinemas, ensured that film technology prioritized lighter complexions in both photography and filmmaking.

The combined use of Shirley Cards, China Girls, and Kodak's choices in film chemistry had widespread implications for how race was depicted in visual media. This bias extended beyond amateur photography, affecting professional filmmaking as well, where Kodak's film stocks dominated the industry.

The rise of color film and the specific choices Kodak made regarding film chemistry had significant implications for how people of different races were represented in visual media. These choices were not just technical decisions but were reflective of broader societal norms and industry practices that prioritized white subjects. The result was a technology that systematically marginalized non-white individuals in visual media, contributing to the reinforcement of racial hierarchies and social inequalities.

Chapter 2: Racial Bias in Kodak Film Stock

2.1 Technical Foundations of Racial Bias

The racial bias in Kodak's film stock can be traced back to the technical foundations of how film captures light and color. Photographic film, a photosensitive material, reacts to light to create an image that is later developed into a visible photograph. The way film responds to light is influenced by several factors, including the composition of the photosensitive emulsion, the sensitivity of the film to various wavelengths, and the chemical processes used in development.

One of the key factors that contributed to the racial bias in Kodak's film stock was the composition of the photosensitive emulsion. The emulsion, responsible for reacting to light, was optimized to be most sensitive to the wavelengths reflected by lighter complexions, making it less effective at capturing those reflected by darker complexions. In addition, the color couplers used in the emulsion were designed to produce dyes that worked well for lighter skin, but distorted darker complexions, often resulting in unnatural or inaccurate color rendering.

The chemical processes involved in developing the film further compounded the problem. Kodak’s development techniques were fine-tuned to enhance colors and contrast in mid-tones, which worked well for lighter complexions but frequently failed to accurately capture darker ones. This resulted in underexposed images where detail and depth were lost, leading to the systematic marginalization of non-white subjects in visual media.

These technical limitations were worsened by the restricted dynamic range of the film, which struggled to balance light and dark areas in scenes featuring both lighter and darker skin. As a result, while lighter complexions were rendered accurately, darker complexions were often underexposed, appearing flattened or lacking in detail.

In addition to this underexposure, the color rendering also faltered, with darker skin tones taking on unnatural shades of red, yellow, or green due to the film’s chemical design.

The impact of these issues had particularly adverse consequences in professional filmmaking. Kodak's dominance in Hollywood meant its film stock was widely used. Hollywood films often featured white actors in leading roles, with non-white actors relegated to secondary or background roles. Non-white actors, when featured, were often poorly lit and inaccurately depicted, further entrenching their marginalization in the film industry. This technical bias in film stock reflected broader societal norms and industry practices that prioritized white subjects, deepening racial disparities in visual media.

2.2 The Shirley Cards and Their Controversy

One of the most significant contributors to the racial bias in Kodak's film stock was the use of “Shirley Cards” for color calibration. These cards consisted of carefully exposed reference images, produced in controlled studio settings, featuring white women as subjects. Lab technicians used these reference sets to standardize the development processes and calibrate film printing machines for color balance and exposure. The name “Shirley” originated from model Shirley Page, a Kodak employee, though later models continued to be referred to as "Shirleys." Always young and white, these women were portrayed with a Hollywood-inspired aesthetic, often wearing glamorous clothing, furs, and bold red lipstick. Consequently, their fair skin tones became the benchmark for "correct" exposure and color balance. However, this focus on light skin meant that darker-skinned subjects appeared underexposed, with muddied and unnatural color casts.

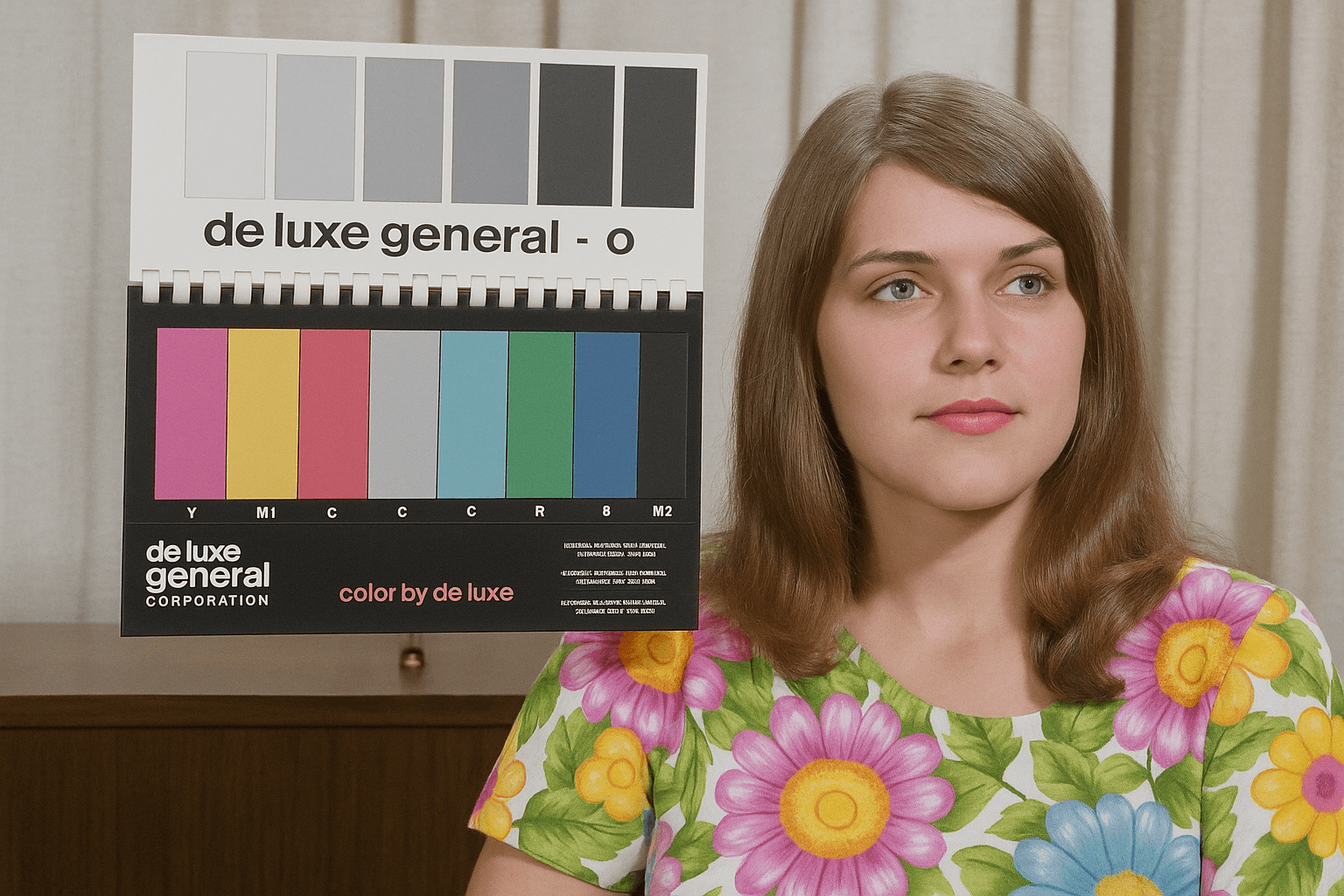

This bias was not exclusive to photography, as the use of "China Girls" in motion pictures similarly reinforced this standard. "China Girls" were images of fair-skinned women included in film leader sequences, used by technicians to test color accuracy in motion pictures.

Like Shirley Cards, the "China Girls" standard perpetuated the bias toward lighter skin tones in the filmmaking process, leading to similar underexposure and distortion of darker skin tones.

The use of Shirley Cards and China Girls for color calibration extended beyond Kodak and was embraced by other film manufacturers as well. This widespread adoption ingrained a bias against darker skin tones throughout the industry, influencing how race was portrayed in visual media. Since these tools were crucial for calibrating both film processing equipment and projection systems, they established a biased industry standard that affected how all skin tones were captured in both still photography and motion pictures. This practice permeated the entire film industry, embedding racial bias into the very technology that shaped visual media worldwide.

In the 1960s and 1970s, photographers, filmmakers, and activists began to criticize the use of Shirley Cards, arguing that they perpetuated racial bias in visual media. This criticism was part of a broader movement aimed at challenging the exclusionary practices of the film industry and advocating for more inclusive representation. In response, Kodak introduced new film stocks like "Vericolor" and "Eastman EXR," which offered extended exposure latitude and improved color accuracy for a broader range of skin tones. Recognizing the issue with the all-white Shirley Cards, Kodak also took steps to address the problem. Photographer Jim Lyon, who joined Kodak’s first Photo Tech Division and Research Laboratories, began incorporating Black models into the testing process, a change that quickly gained traction. Around the same time, other film companies had developed their own versions of Shirley Cards, and Kodak soon followed by producing multiracial reference cards featuring Black, Asian, Latina, and White models.

The controversy surrounding Shirley Cards and "China Girls" underscores how technological decisions can perpetuate social biases and contribute to the marginalization of specific groups. By basing the standard for color balance on white skin tones, these tools reinforced the exclusion of non-white individuals from accurate depiction in visual media. This exclusion had significant social consequences, reinforcing racial hierarchies and deepening the marginalization of non-white individuals in society.

2.3 The Feedback Loop of Technology and Practice

This relationship between film technology and industry practices created a feedback loop that perpetuated racial bias. As film stock and lighting techniques were tailored to better suit white subjects, these practices became the industry norm. In turn, the widespread adoption of these standards solidified the prominence of white subjects in visual media, further sidelining non-white individuals.

This feedback loop extended beyond technical considerations and shaped the content of visual media itself. Since the technology favored white subjects, filmmakers and photographers were more likely to feature them, leading to limited visibility for non-white individuals. This underrepresentation deepened societal racial biases, as visual media plays a crucial role in shaping public perceptions and cultural narratives.